The below is a copy of my essay submission for a university political science course. As the essay is just under 5,000 words, the full piece is available after you click the “Continue Reading” link:

Introduction

In the 19th century, John Stuart Mill wrote in On Liberty that, “The worth of a State, in the long run, is the worth of the individuals composing it,” such that, “Is it not almost a self-evident axiom that the State should require and compel the education, up to a certain standard, of every human being who is born its citizen?”[1] This liberty in establishing the value and merit of education is mirrored in Canada’s Constitution Act (1867) where it states, “In and for each Province the Legislature may exclusively make Laws in relation to Education, subject and according to [several]… Provisions.”[2] Thus, an important distinction as to which level of government should be given the authority to design and implement policy is required, such that decision-making is either centralized to the federal level or decentralized to the province/territories.

An assessment of Canadian education and environmental policy should make clear whether current policy is competitive internationally and whether our current administration has addressed the ‘national concern’, defined as, “a “singleness, distinctiveness, and indivisibility that clearly distinguishes it from provincial concern.”[3] This paper demonstrates that education and environment policy are a national concern and evaluates that new public management (NPM) would be a plague to current public administration (PA).

New Public Management

Since 1963, NPM in Canada has resulted from the demand for improved management of public services, specifically the role of PA. The focus of NPM has been reducing debt and deficit problems of the fiscal government, maintaining the divide between politicians and its citizens, and managing expectations both domestically and internationally as a result of globalization. In turn, NPM advocates for privatization, deregulation, decentralization, and contracting out of public services, which has reduced the comfort of patronage. Thus, the dilemma with NPM eliminating Canadian PA concerns equity vs. efficiency, fairness vs. responsiveness, and due process vs. service-quality.

While the organizational mechanisms of government have become increasingly complex, proponents of NPM accuse PA for yielding too much power over its politicians and thus advocate for a re-engineering of the whole apparatus of government and its management. This increasing complexity is largely a result of globalization and international trade. However, benefits from economic efficiency should not be mixed with political administration, as by definition, an economy is subject to the business cycle, which sees periods of expansion followed by periods of contraction. Therefore, the only merit NPM should have with respect to PA is in fact an argument made by the most influential NPM proponents, Osborne and Gaebler, who argue “government must steer, not row.”[4] This draws from the idea of Osborne’s concept that governments should be “uncoupling policy and regulatory functions (“steering”) from service-delivery and compliance functions (“rowing”).”[5] However, Osborne’s paper demonstrates the conceptual flaw in his consulting advice, “Organisms are shaped by their DNA: the coded instructions that determine who and what they are. DNA provides the most basic, most powerful instructions for developing an entity’s enduring capacities and behaviors.” While comparing PA to that of a live organism that lives, grows and most importantly dies, this last aspect of an organism’s life is the greatest strength and weakness of Osborne’s argument. In light of what Janet and Robert Denhardt states, Osborne’s consulting advice should “Recognize that accountability isn’t simple… [PA should] Think strategically, act democratically.”[6] Thus, NPM should only attempt to assist in rowing straight, rather than steering PA into hands of the elite.

In light of the above, one should not be so quick to assume that operating and managing government on a more businesslike footing will produce a greater outcome in a consistent manner over extended periods. NPM should note the empirical evidence of economic cycles compiled in (Glubb, 1978) which concluded that the life cycle of leading nations amounted only to ten periods, each approximately twenty-five years, concluding in six epochs.[7] Thus, to apply a boom-bust mentality to the operation and management of PA is an ideology that in itself, is inefficient, unresponsive and lacks long-term accountability. Similar to drug trials and scientific experiments, for NPM to mix its three Es[8] with those values held by PA, this would alter the existing DNA. However, those left accountable will not be high-priced consultants, like that of David Osborne, but those in PA who trusted the advice and models of NPM.

Education Policy

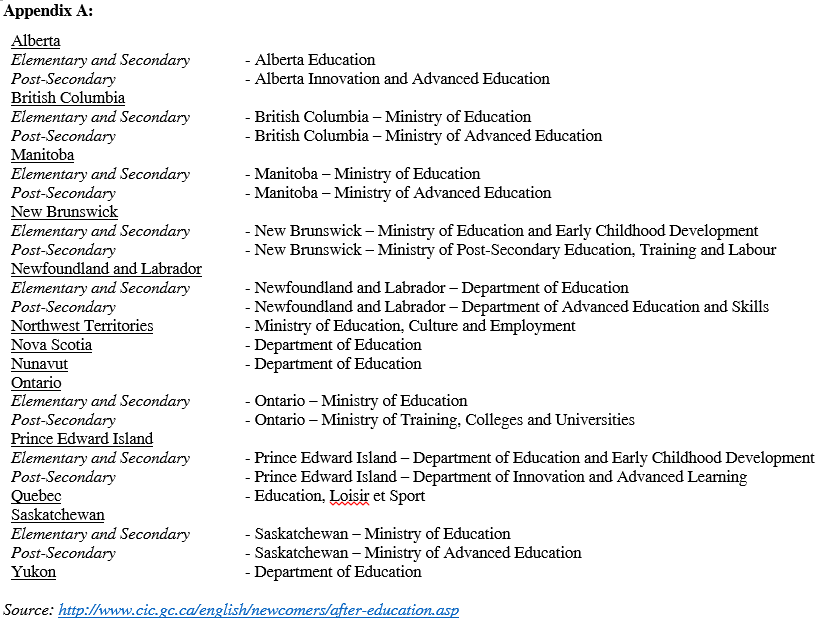

In Canada, education policy is decentralized to ministries of the 13 provinces and territories. However, this decentralization has not been a result of the Constitution Act (1867) and not NPM. Even though the educational systems are generally similar across the ministries, slight variations are natural and should be maintained within acceptable limits. While nearly all of the ministries are split between handling elementary and secondary schools, and post-secondary schools[9], the Council of Ministers of Education (CMEC) was established in 1976 to ‘contribute to the exercise of the exclusive jurisdiction of provincial and territories over education’, and to promote cohesion of education policy.

The CMEC draws all ministers of education to collaborate on pan-Canadian educational priorities. Similar to the position of Mill that ‘the State should require and compel the education, up to a certain standard’, the CMEC has identified that the government’s role is one in which “Public education is provided free to all Canadians who meet various age and residence requirements.”[10] Therefore, improvement in education policy should stem from within the ministries and reflect on what Sir Michael Barber, chief education advisor of Pearson, states: “Governments all around the world are under pressure to deliver improved learning outcomes because they are increasingly important ingredients of success. As a result, education ministers are on the search for evidence of what works more than they ever were before.”[11] This pressure to deliver improved learning outcomes falls upon the shoulders of deputy ministers (DMs).

In terms of PA, the education minister of each province/territory is almost always an elected member of the Legislature and appointed to their position by the government leader of their jurisdiction. These DMs often have continuous experience in government and usually are experts within the administration in a parliamentary system of ministerial responsibility and administrative accountability. Thus, this presents the debate of NPM vs. PA: the accountability of DMs who, as the most senior public servant, usually through patronage, is expected to assume a position of independence and must reach a decision with approval from nominal superiors. In regards to education policy, it appears that, conceptually, DMs are a plague to decision-making since their decisions can be hampered by bureaucracy at the federal level, e.g. aligning provincial education policy with advice from the CMEC, and at the municipal level, e.g. democratically elected members of school boards may wish to pursue an alternative objective to that of the DM of the province. Because of this potential upward and downward pressure, the DMs decision-making has been partially alleviated with the release of CMEC’s Learn Canada 2020[12], a framework that ‘provincial and territorial ministers of education will use to enhance Canada’s educational systems, learning opportunities, and overall education outcomes’. It should be viewed that the CMEC is not a result of NPM, rather it is the opposite in that it is an additional level of bureaucracy in the decision-making of education policy in Canada.

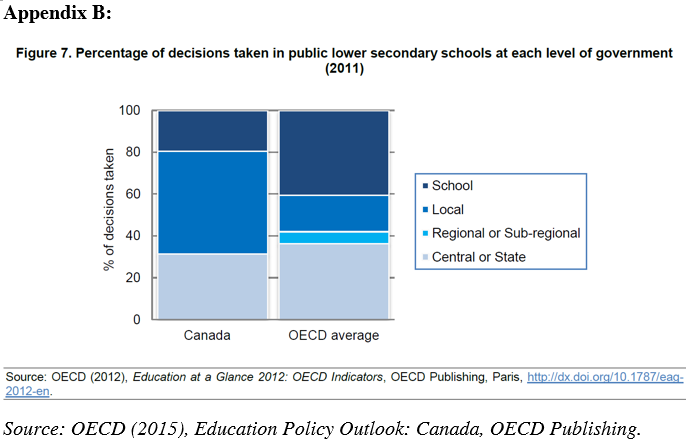

This additional layer of bureaucracy helps prevent education policy from undermining the directions to decentralize decision-making, as instructed by the Constitution Act (1867), and assists the DM’s decision-making in educational, administrative and financial management and support facilities, along with defining both the educational services to be provided and the policy and legislative framework. However, as a result of decentralized nature, the (OECD, Education Policy Outlook: Canada, 2015) indicates that ‘49% of the education policy decision-making takes place at the board/district level, 31% at provincial/territorial level, and 19% at the school level’[13]. It is important to highlight the minority 19% decision-making power at the school level as provincial-municipal conflict can arise as a result of curriculum. Curriculum is set by the province and administered by the schools, however, as (Sium, 2014) indicates, “Split grades are nearly impossible for teachers to handle under the province’s rigid, jam-packed curriculum…. Teachers with split grades say they feel stressed and rushed.”[14] If conflict exists at the local level, should authority be solely administered by the ministries of education? This appears to be a conflict that is not exclusive to Canada as the curriculum of education in the US is heavily institutionalized and protected.[15] Furthermore, decision-making at the school level in Canada is lower than the OECD average and at the provincial/territorial level it is much higher than the OECD average. Appendix B depicts the decision-making in Canada compared with that of the OECD average, further supporting the previous point that the PA of education policy in Canada has largely been a plague in principle but the added level of bureaucracy through CMEC Learn Canada 2020 has alleviated conflicts.

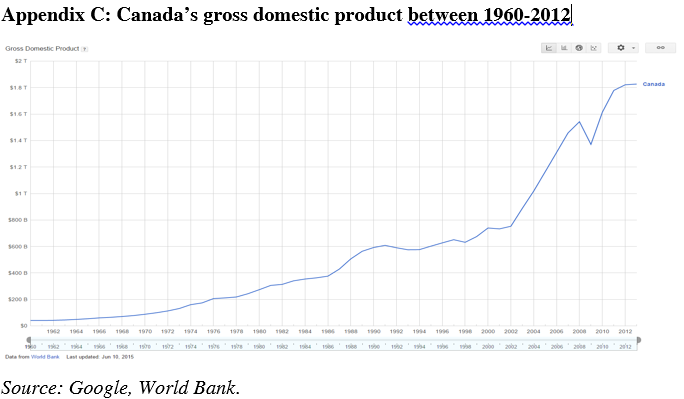

In terms of economics, why is education policy an investment rather than being viewed as an expenditure? The (OECD, Education Policy Outlook: Making Reforms Happen, 2015) indicates that, “Expenditure on education has held up well during the [financial] crisis: education is seen as an investment and one that is increasingly important. Governments increasingly examine how to make the best use of that investment and ensure that it is effective, fair and efficient.” This implies that policy-making has been closely tied with a nation’s gross domestic product (GDP)[16] and specifically, the expenditure on Canada’s education policy has been formulated closely alongside other government policies. However, evaluating education policy in terms of education expenditure as a percentage of GDP should be considered invalid, especially since the anticipated level of educational funding would be more optimistic during periods of economic growth, and vice versa. Thus, traditional concepts of payoff and return on investment cannot be applied in this instance as economic output is dependent on both endogenous and exogenous factors. Therefore, the skills attained between elementary to post-secondary schools, which would imply the level of future economic prosperity, would depend on current educational spending, which is currently closely tied to the state of the current fiscal budget. Canada’s GDP (expenditure-based) between 1960-2012:

In terms of literature, the Pan-Canadian Education Indicators Program (PCEIP) indicates through (Statistics Canada, 2014) that government expenditure on education is both efficient and effective.[17] Expenditure per student at the primary level was US$9,714 and US$10,618 at the secondary level; in comparison, the OECD averages were US$8,296 and US$9,506 respectively. Most striking is the level of expenditure per student at the university level. In Canada, this was US$27,102, almost double the OECD average of US$13,958, yet has this yielded any benefits?

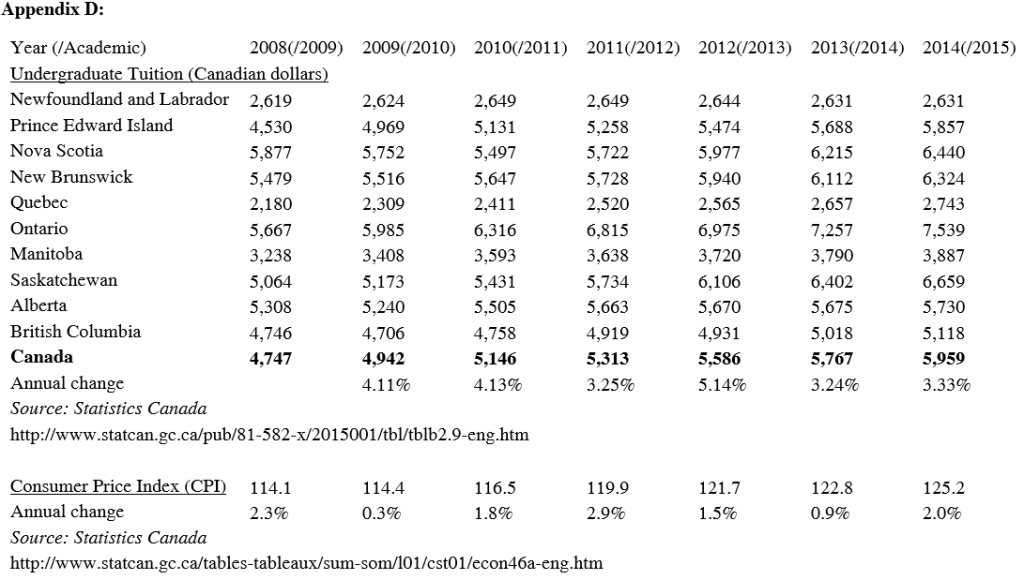

At the post-secondary level of education, Appendix D is a table of the average undergraduate tuition cost across the provinces/territories for the six-year period between the 2008/2009 and 2014/2015 academic years. In the six-year period, tuition for undergraduate studies grew an average of 3.86% per annum, whereas the Canadian consumer price index (CPI) shows that there was only a 1.57% growth per annum. As a result, PA has been unable to negate the increasing opportunity cost of foregoing entering the workforce after secondary school as a result of increased cost of living while pursuing an undergraduate degree. However, this increased opportunity cost would be further exacerbated by NPM as it strives for the contracting-out of services, which in turn are profit seeking.

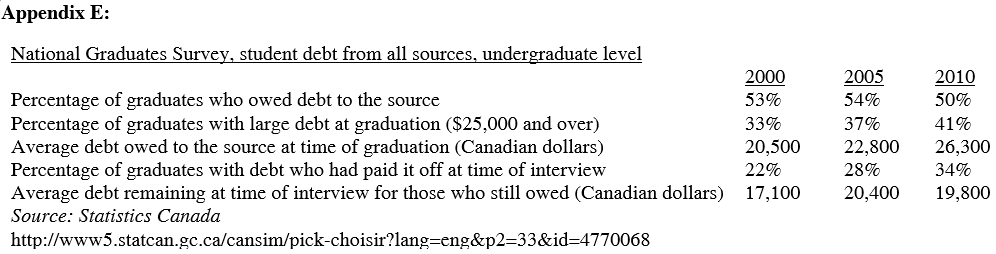

Appendix E shows that although there has been a decreasing percentage of undergraduate students who owed debt as a result of undergraduate studies, there appears to be a greater disparity in the well-being of post-secondary students: firstly, graduates with a large debt load[18] increased from 33% in 2000 to 41% in 2010, and secondly, the average amount of debt owed increased from $20,500 in 2000 to $26,300 in 2010. These results question the efficacy of PA of post-secondary educational funding. Furthermore, Statistics Canada indicates two worrying indicators[19]. Firstly, there has been a rising share of employees earning the minimum wage in Canada. As of 2013, the proportion of all paid employees earning the minimum wage was 6.7%, up from 5.0% in 1997[20]. Secondly, young employees were most likely to be paid at minimum wage. As of 2013, 50% of employees aged 15 to 19 years old were paid at minimum wage, and among those, 13% were aged 20 to 24. Provincially, Prince Edward Island and Ontario had the highest proportion of employees paid at minimum wage at 9.3% and 8.9% respectively, while Alberta had the lowest at 1.8%. This further exacerbates the problem for PA in addressing the opportunity cost dilemma that post-secondary applicants face, an issue that needs to be addressed at the federal level rather than provincial. Thus, NPM would not be of assistance here, rather an additional level of bureaucracy.

According to the CMEC website, publicly funded universities in Canada set their own admissions standards and entry requirements. Furthermore, universities operate with considerable flexibility in the management of their financial affairs and program offerings. This implies that if the cost of tuition has seen such strong growth some should question the university’s admission criteria and allocation of university applications from post-secondary institutions across Canada. According to Western University’s Tuition and Ancillary Fee Schedule for 2015-2016, an undergraduate first year’s tuition for an arts program costs $7,576.74, while that of an international student costs $24,851.74 or 228% more.[21] This implies that if post-secondary institutions were to face budget cuts from their ministry of education, their admissions team could allow a greater percentage of international students to prospectively make up the gap in funding from their ministry of education. However, this outcome would neither be attributable to NPM nor PA, but could be viewed as a natural form of checks and balance.

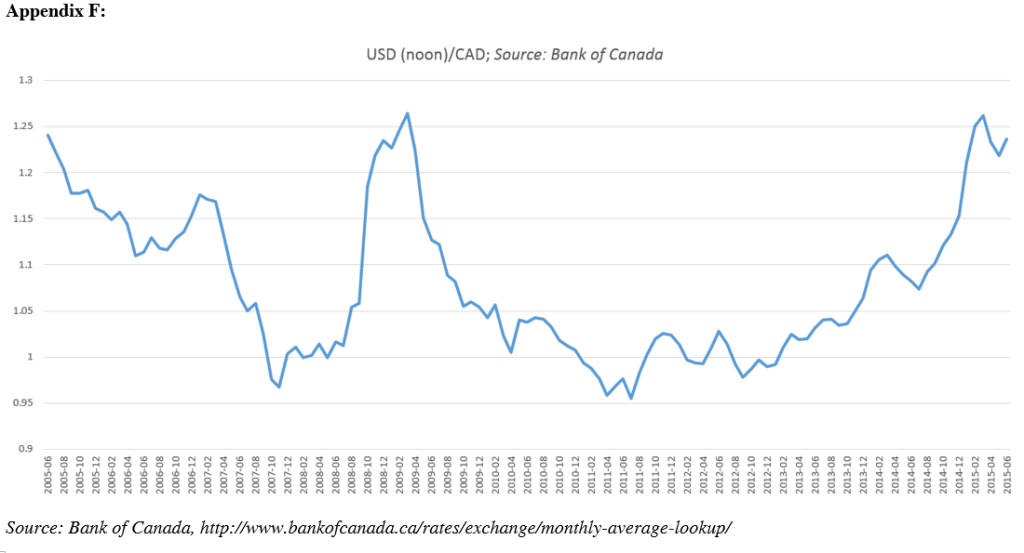

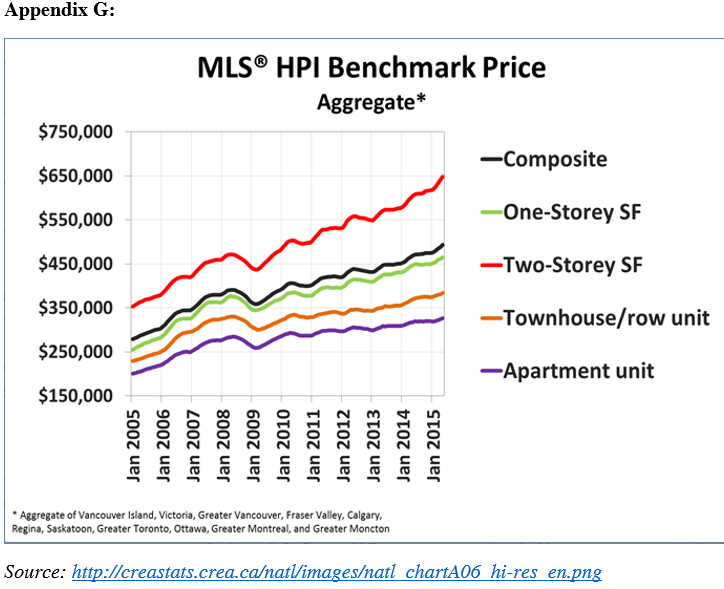

In addition to student debt, there have been increasing housing prices across Canada[22]. If NPM is to prevail, the neoconservative idea on ownership of private property faces increasing systemic issues in regards to affordability and reliability. In this regard, NPM has failed on account of accessibility. Ownership of private property further exacerbates the issue of private debt for young adults graduating from post-secondary schools.

According to the Canadian Real Estate Association, Appendix G shows the growth of house prices across Canada using the ‘MLS HPI Benchmark Price’. As a result, recent post-secondary graduates who have taken on a mortgage, in addition to their student debt, have prospectively been issued a large amount of debt during a period of historically low cost of borrowing. Additionally, some could say that the stability of their current mortgage repayments are being supported by a weak Canadian dollar and recent drop in the price of natural resources. While this is not directly a result of education policy, PA should factor in material aspects of post-secondary student’s future economic decisions. Thus, would NPM be a panacea? It appears not. One could view that, systemically speaking, the economic conditions of today establish a competitive labour force more willing to provide their skills at respectively lower wage as a result of their inherited private debt. It would be far-fetched to assume a politician, like Thatcher or Reagen, engineered such a framework. Furthermore, this is beyond the conceptual ideology of NPM and as a result of the economic conditions, PA would face enemies in cleaning up the window dressing, particularly in light of what Machiavelli warned: “For the reformer has enemies in all those who profit by the old order, and only lukewarm defenders in all those who would profit by the new order.”[23]

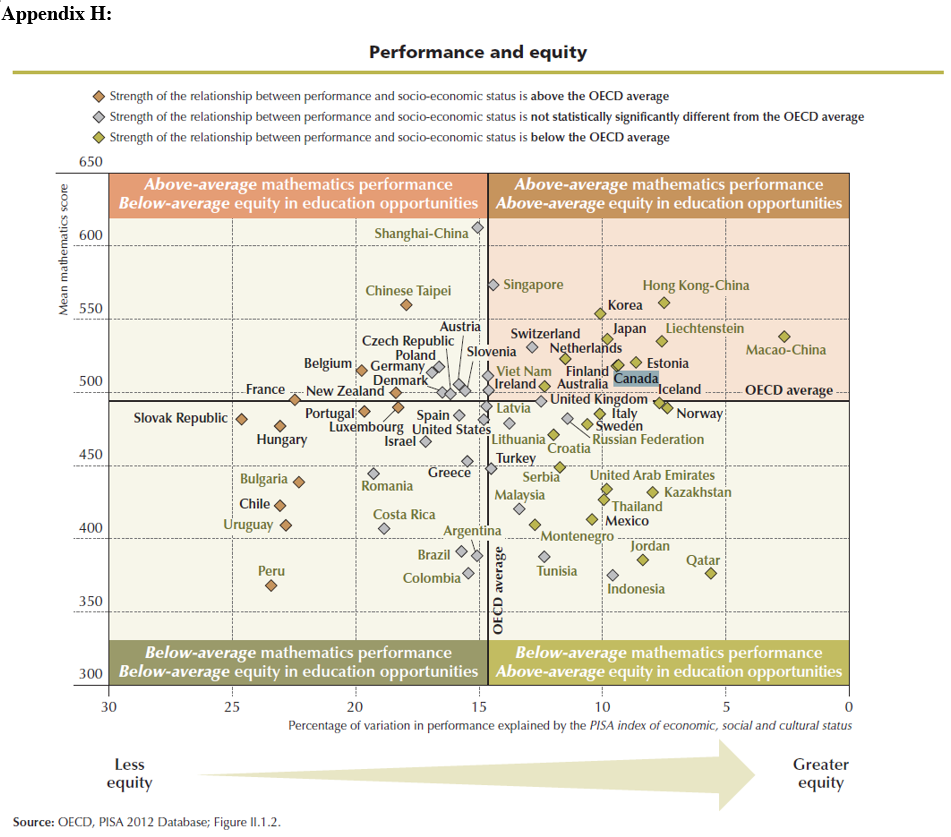

While the economics of education policy in Canada is questionable, the performance indicators of education in Canada stand in stark contrast. Statistics Canada declared in 2012 that 92% of the population between 25-34 years old had attained at least an upper secondary education and 57% had attained post-secondary education.[24] In comparison to OECD countries, upper-secondary education attainment was an average of 82% and 39% for post-secondary attainment.[25] More specifically, the 2012 OECD PISA results indicate that, “The PISA results of several countries demonstrate that high average performance and equity are not mutually exclusive.”

As Appendix H highlights, Canada is one of the top ranked OECD countries in equity. In fact, a highlight from the 2012 PISA report is in terms of teacher-student engagement: “Canada is more successful in this regard: 60% of students in Canada reported that their teachers often present problems for which there is no immediately obvious way of arriving at a solution.”[26] This indicates that the PA of education policy is performing well, specifically concerning curriculum. Therefore, if NPM is arguably a plague to the PA of education, is the environmental policy of Canada in a similar situation?

Environmental Policy

The environmental policy of Canada is derived from the Constitution Act (1867), similar to that of education policy. (Olewiler & Field, 2011) highlights that environmental policy in Canada is six-fold[27]:

- Incentive-based policies are much less common than command-and-control policies.

- There has been a reluctance to impose specific standards.

- Environmental legislation in Canada has been based on a co-operative model of negotiation between the government regulator and the polluting party.

- Environmental legislation in Canada has been primarily enabling rather than mandatory.

- Negotiation and moral suasion have been used to achieve compliance with environmental targets.

- Jurisdiction over the environment is not always defined. Conflict among the levels of government and inaction can arise as a result.

While the education policy of Canada is empirically successful, its complexity in decision-making is similar to that of environmental policy. Therefore, the sixth and last point is most relevant especially as NPM aims to replace the equity of PA with efficiency of operation, it is essential to mitigate the conflict between levels of government that would have resulted in inaction.

The division of constitutional powers with respect to the environment is set out by the Constitution Act (1867) which provides provinces with the power of local works, property and civil rights administered within the provinces[28]. Thus, matters of a local or private nature are conferred by the province over provincially owned lands and resources. Furthermore, an amendment in 1982 to the Constitution Act gave provinces even greater authority over its natural resources. This increased authority arguably pulls environment policy away from the reaches of NPM and relies on the existing merits of PA. Thus, similar to education policy, “The key to understanding Canadian environmental policy is to recognise that most regulatory powers applicable to the environment lie with the provincial governments.”[29] On the other hand, environmental policy of Canada is not as decentralized as that of education policy and as a result, NPM should be incorporated to efficiently assist conflicts arising from inter-provincial pollution flows (where pollution flows across provincial boundaries), the federal government must act in all parties’ best interest to mitigate tensions. Furthermore, international treaties are handled at the federal level but implemented at the provincial level, a distinction that could cause conflicts if the province were to disagree with the federal stance on environmental policy. International treaties and interests are aspect that education policy does not concern itself with. In fact, it highlights a stark contrast in the PA of both policies: education policy faces internal accountability to Canadian citizens and environmental policy faces external accountability to international treaties and supranational organizations. Thus, it could be argued that NPM is more applicable in addressing the pitfalls of the public administration of Canadian environmental policy.

Policy harmonization is not required but would clearly benefit by reducing tensions, particularly in light of economic interests. The natural resource industry is one of the primary economic rents of Canada, an industry particularly prevalent in Alberta. If public servants of the federal government negotiated itself into an international treaty that required the nation to curtail its natural resource extraction, during a period of fiscal deficits in Alberta, it would clearly not be in Alberta’s interest to implement such a policy and thus, federal—provincial conflict would arise[30]. Yet what would occur in this instance? The Judiciary would be required to intervene and decide whether certain issues are jurisdictions of ultra or intra vires. Thus, in situations of concurrency, the doctrine of paramouncy would prevail and potentially exacerbate federal-provincial tensions. Historically, while there have been very few legal decisions regarding environmental legislation, more challenges from the provincial governments are expected if environmental legislation moves from the level of suggested guidelines to specific standards and/or incentive-based policies.

In comparison to education policy, two constitutional powers, with respect to environmental policy, remain in conflict in Canada. Firstly, there is a lack of clarity and secondly, there has been an overlap of jurisdictional responsibilities between the provincial and federal level, prompting inefficiencies and unnecessary bureaucracy. This is certainly an aspect NPM can address in harmonizing the conflicting objectives between federal and provincial administration. Thus, concurrent regulations that are consistent through identical policy objectives and similar policy instruments would minimize federal-provincial tensions. As a result of this lapse in PA, NPM occurred through the Harmonization Accord of 1998[31]. This accord improved the coordination of environmental policy, reduced conflict and overlap, and promoted joint initiatives on the environment.

In terms of governance, (Olewiler & Field, 2011) indicate that the governing party, under a parliamentary system with a majority government, has a lot of control over the legislative agenda. This infers that if the governing party support a curtailing of natural resource extraction, the likelihood of legislation being approved is strong. However, this brings up the issue of federal-provincial conflict on the loss of economic benefits to the province as a result of such a legislation. Unlike the United States (US), Canada does not have an equivalent checks and balances system like that of the US President and Congress. In the US, Congress can write and pass laws that need not have the support of the President; however, this is generally impossible in Canada as the executive and legislative branches, under a majority government, are essentially one. Therefore, PA can hardly be blamed for the lack of a checks and balance on environmental policy, rather, it is could be said that a lack of NPM is responsible for ensuring public pressure on the government being accountable on environmental issues. Unfortunately, PA in Canada is elite-dominated in a form which is corporatist, such that in the above example regarding natural resource extraction, corporate interests (the elite) would support the neoconservative ideology and it would not be in the interest of NPM to support consociation.

Empirical evidence demonstrates that is has been the failure of PA to establish an environmental policy that is competitive internationally. Rather, (Development, 2013) ranked Canada 27th out of the world’s 27 wealthiest countries[32], which ‘measures the impact of policies on the global climate, fisheries, and biodiversity’, such that, weaknesses of Canadian policy are as follows:

- High greenhouse gas emissions and fossil fuel production rate per capita (52.2 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent; rank: 25);

- Has not ratified the Kyoto Protocol on climate change;

- High fossil fuels production rate per capita (29 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent; rank 25);

- Low gas taxes ($0.34 per liter; rank: 26);

- High fishing subsidies (rank: 26); and

- Poor compliance with mandatory reporting requirements under multilateral environmental agreements relating to biodiversity (rank: 24).

Canada ranks poorly among other organizations, as the Climate Action Network Europe ranked Canada 58th out of 61 countries (the last being Saudi Arabia) in their 2015 Climate Change Performance Index[33]. Thus, the question remains: if Canada’s environmental performance ranked so poorly and educational performance ranked so highly, would NPM assist policy makers in delivering better policies and results to its stakeholders? Based on the limited evidence, yes. However, it would be farfetched to imply that simply due to observed rankings (which are subject to interpretation) and research that the NPM assists Canada in performing competitively in key areas (e.g. education and environment). Public scrutiny of education and environment differ drastically as citizens are able to quantify the immediate benefit from a better education policy, e.g. higher skills, than quantify the lasting effects on global warming for their future generations.

If the CMEC was successful, did Environment Canada[34] (EC) fail to achieve a similar feat? The demise of the importance of EC resulted from several PA difficulties, specifically issues of bureaucracy. (Olewiler & Field, 2011) indicates that from the period 1971 to 1986, EC suffered from a lack of leadership as it went through 10 different ministers and many reorganizations. Furthermore, EC was limited to duties, powers, and functions, instead of being assigned by law to any other department, branch, or agency of the federal government. As the EC was perhaps borne out of subjective responsibility and operated with little accountability, EC could not compete with federally appointed agencies with greater statutory powers. Furthermore, EC was classified under the federal budgetary “envelope” of “social development”, implying that EC competed with health and welfare departments for federal funding. However, competition within the social development envelope was particularly competitive since it was a major recipient of federal funds.[35] This is a failure of EC’s leadership rather than the need for NPM to intervene.

In contrast to the CMEC, EC suffered from horizontality as its role overlapped other agencies within environmental objectives. Recently, Canada’s Green Plan, a national strategy and action plan for sustainable development, similarly launched with strong growth only to falter. It would not be wholly correct to state that NPM would improve environmental policy in Canada, rather NPM would prevail only as a result of, empirically speaking, the structural and leadership failures of PA thus far.

Conclusion

While drawing comparisons between Canada’s education and environmental policy may yield relevant observations as to whether NPM has been a panacea or plague to PA, how has the “national concern” been addressed? On aggregate, it is hard to dispute that education policy and environment policy are respectively and collectively a ‘national concern’ on the simple principle today’s decisions impact our future options. In fact, the fragmentation of policymaking occurs simply as a result of the Constitution Act (1867) and a question of whether root of the cause lies with NPM or PA would be unfair to both principles. Thus, it appears that NPM and PA should, in concept and reality, be treated as mutually exclusive ideologies, rather than complementary. Both NPM and PA are well-respected principles, but to pick and choose between presents a form of inefficiency in itself.

Bibliography

Cahn, S. (2015). Political Philosophy, The Essential Texts (3rd Edition). New York: Oxford University Press.

Development, C. f. (2013). Commitment to Development Index: Canada. Washington: Center for Global Development .

Glubb, S. J. (1978). The Fate of Empries and Search for Survival. Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons Ltd.

Inwood, G. J. (2011). Understanding Canadian Public Administration (4th edition). Toronto: Pearson Education Canada.

OECD. (2015). Education Policy Outlook: Canada. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2015). Education Policy Outlook: Making Reforms Happen. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Olewiler, N. D., & Field, B. C. (2011). Environmental Economics (3rd Canadian Edition). New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Sium, B. (2014). How Black and Working Class Children Are Deprived of Basic Education in Canada. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Statistics Canada, C. (2014). Education Indicators in Canada: An International Perspective. Ottawa: Minister for Statistics Canada.

[1] Pages 807 and 801 of J.S. Mill. On Liberty in (Cahn, 2015).

[2] Section VI part 93 of the Constitution Act (1867).

[3] For further information, please refer to the Supreme Court of Canada, 1 S.C.R. 401 (1988).

[4] Page 112 of (Inwood, 2011).

[5] From a David Osborne paper, Reinventing Government: What a difference strategy makes, addressed to the United Nations: http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan025253.pdf

[6] Page 114 of (Inwood, 2011).

[7] For further reading, please refer to (Glubb, 1978).

[8] The three Es are: efficiency, effectiveness, and economy.

[9] Please refer to Appendix A for a full list of the recognized ministries and departments of education in Canada.

[10] From the CMEC website: http://www.cmec.ca/299/Education-in-Canada-An-Overview/

[11] From page 2 of the 2014 edition of The Learning Curve, published by Pearson can be found here: http://thelearningcurve.pearson.com/content/download/bankname/components/filename/The_Learning_Curve_2014-Final_1.pdfa

[12] For further information, please refer to: http://cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/187/CMEC-2020-DECLARATION.en.pdf

[13] Page 14 of OECD (2015), Education Policy Outlook: Canada, OECD Publishing.

[14] Page 70 of (Sium, 2014).

[15] Failure of the US educational system and the protection of its national curriculum is documented in the film: Waiting for “Superman”, directed by Davis Guggenheim.

[16] Please refer to Appendix C for a historical chart of Canada’s GDP between 1960 and 2012.

[17] For more information, please see: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/81-604-x/81-604-x2014001-eng.pdf

[18] In the Statistics Canada national graduates survey, a large debt load is defined as $25,000 and over.

[19] For further information, please see: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/140716/dq140716b-eng.htm

[20] Additionally, the proportion of young employees aged 15 to 19 who were paid the minimum wage rose from 30% in 2003 to 45% in 2010.

[21] For further information, a full list of Western University’s tuition can be found here: http://www.registrar.uwo.ca/student_finances/fees_refunds/fee_schedules.html

[22] Recent migration trends, indicated by the appreciation of the Canadian dollar in Appendix F, have further driven up housing prices in Canada, especially in British Columbia and Ontario.

[23] Pages 276-277 of Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, in (Cahn, 2015).

[24] For further information, please see: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-402-x/2012000/chap/edu/edu-eng.htm?fpv=1821

[25] Page 19, Education outcomes of Annex B, OECD (2015), Education Policy Outlook: Canada, OECD Publishing.

[26] Page 22 of the 2012 PISA results: http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results-overview.pdf

[27] Chapter 15 – 1 and 2 of (Olewiler & Field, 2011).

[28] Section 92 of the Constitution Act (1867): http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const//page-4.html#docCont

[29] Chapter 15 – 3 of (Olewiler & Field, 2011).

[30] It would not be in Alberta’s interest as revenues from the taxation of natural resource extraction and process would be lower as a result of lower extraction, unless the free market price of oil were to behave irrationally. Furthermore, prospectively lower revenues during a period of fiscal deficits would not be welcome.

[31] For further information, please see: http://www.ccme.ca/en/resources/harmonization/index.html

[32] For further information, please see: http://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/archive/doc/CDI_2013/Country_13_Canada_EN.pdf

[33] For further information, please see: http://www.caneurope.org/resources/latest-publications/ccpi

[34] Environment Canada was established in 1971 to bring together a number of different federal agencies that had environmental responsibilities.

[35] Social development received 35% of total federal spending in the 1970s to 1980s.